A la demande de nombreux collègues non-francophones (Anglais, Américains, Finlandais, Italiens, Russes) j’ai rédigé une version anglaise de mon précédent papier sur les conséquences économiques du confinement (lock-down). Cette version ayant bénéficié de nombreuses améliorations, je l’installe sur Les Crises afin qu’elle serve désormais de version de références.

————————————————————————————————————————-

The lock-down economy: prelude to a major depression?

Jacques SAPIR

Professor at EHESS-Paris

CEMI – Robert de Sorbon centre

The coronavirus epidemic strikes the imagination: medias are filled with images of hospitals in distress, and much of the world experiences unprecedented partial or total lock-down. Beyond the human aspect, with its dramas, its pain, there is also the question of the economic cost of this epidemic[1], and especially of lock-down measures[2]. We now, since the Spanish Flue of 1918-1920 that pandemics can have a distinct economic impact even if the death number is quite restricted[3]. We also know that the use of non-pharmaceutical interventions (i.e. quarantine and lock-down) is improving the situation[4]. Nevertheless these measures also have a cost. The case of France, which is not unique in Europe, is from this point of view extremely interesting.

1. A Significant economic impact

It is clear today that the impact of the coronavirus epidemic will be significant. The confinement of the population has put a stop to a large part of production in France. Another part of the production was affected by the slowdown in production in countries with which we have a lot of economic trade and the lack of spare parts. Telework, often presented as a quick fix, is not applicable in many industries, and it is done with a sharp drop in productivity. Finally, the end of confinement will not immediately mean a return to normal. The end of confinement will be gradual, and so will the return to a normal rate of activity. This impact can therefore be estimated. We know that there are already more than 4 million workers on partial unemployment in France. INSEE, the national statistical bureau, published estimates on March 26[5]. The OFCE, a well-known institute linked to the Higher School of Political Sciences (Sciences Po) has also produced estimates[6]. INSEE and OFCE estimates differs, and not only because assumptions are different but also because we have a significant difference in method. OFCE is computing major a demand shock. One not denies that such a shock exists. But, the lock-down of the society is mostly inducing a supply shock by the physical closing of activities and plant. This is what has been observed in China in the Hubei province[7]. The IMF has noted: “What started as a series of sudden stops in economic activity, quickly cascaded through the economy and morphed into a full-blown shock simultaneously impeding supply and demand—as visible in the very weak January-February readings of industrial production and retail sales. The coronavirus shock is severe even compared to the Great Financial Crisis in 2007–08, as it hit households, businesses, financial institutions, and markets all at the same time—first in China and now globally.[8]”

Economic policy, under lock-down situation[9], as recommended by the IMF is quite interesting and consistent with a war economy. Economic policy is to be mostly concerned by guaranteeing the functioning of essential sectors that is maintaining health care, food production and distribution, essential infrastructure, and utilities must be maintained. This could involve direct actions by governments to provide key supplies through recourse to wartime powers with conversion of industries, or selective nationalizations like that was possible in the US through the Defense Production Act. Rationing, price controls, and rules against hoarding may also be warranted in situations of extreme shortages. Then, another priority is to provide enough resources for people hit by the crisis. Unemployment benefits should be expanded and extended. Cash transfers are needed to reach the self-employed and those without jobs. Then, governments have to prevent excessive economic disruption.

We consider, then, that the supply shock is probably the worse in the lock-down situation. We will then discuss the different estimates and also presents our own estimates.

2. A huge economic shock

First of all, it is clear that the French economy is to suffer major a shock with the society lock-down, and a shock that is to be greater the longer the lock down will be implemented. We will begin by looking at the INSEE estimates disclosed by March 26th.

Very clearly, the sectors most affected will be industry and construction. INSEE estimates the loss of activity at -52% for industry and -89% for construction.

Table 1

Loss of economic activity linked to the lock-down

| Economic sectors | Share in GDP | Assumption of activity loss

(in %) |

Impact on activity loss (in GDP %) |

| Agriculture and food-processing industry | 4% | -4% | 0,0%- |

| Industry without food-processing | 12% | -52% | -5,0% |

| Construction | 6% | -89% | -6,0% |

| Services | 56% | -36% | -20,0% |

| Non-market services | 22% | -14% | -3,0% |

| Total | 100% | -35% | -35,0% |

Source: INSEE https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4471804

These figures however are probably below the reality (Annex I)[10]. Production losses in agriculture and services are underestimated. Certain services, those linked to tourism, hotels and restaurants, are much more affected than in INSEE estimates. By the way, we should add that the impact of this shock will be different depending on whether we think of large companies or SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) and VSEs (Very Small Enterprises). The loss of income for VSEs and SMEs is dramatic. And, we tend to forget that SMEs and VSEs are the first employers in France. According to these estimates, for the whole of 2020, the loss of production could reach -6.5% of GDP for a lock-down period of 6 weeks and -8% for 8 weeks.

Table 2

Lock-down impact on quarterly and yearly GDP

| Duration of lock-down | Impact on quarter GDP | Impact on yearly GDP |

| One month | -12,0% | -3,0% |

| Two month | -24,0% | -6,0% |

Source: INSEE, https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4471804

The OFCE estimates, because they concentrated on a demand shock are slightly less severe.

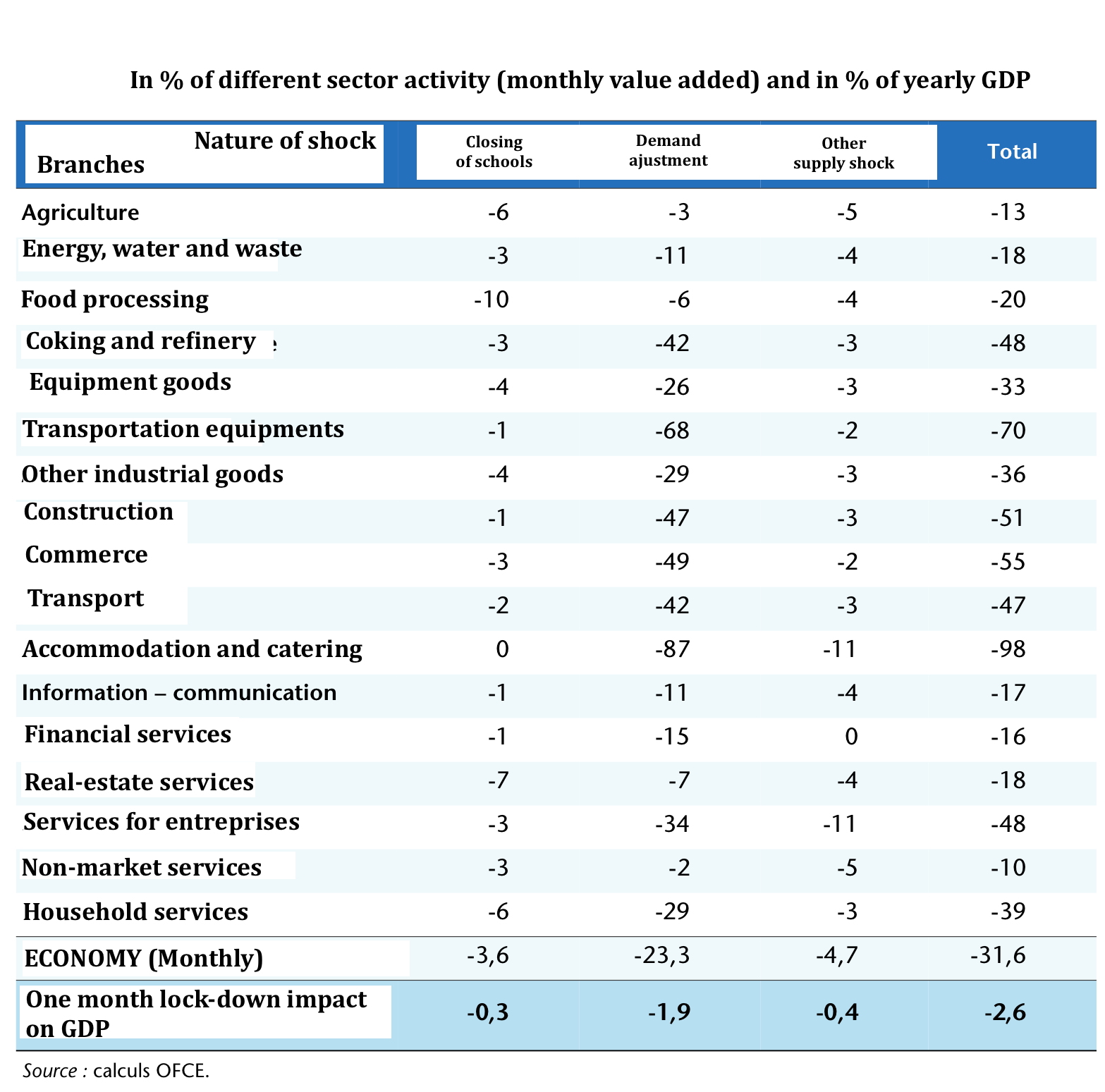

Table 3

OFCE estimates

OFCE, « Evaluation au 30 mars 2020 d l’impact économique de la pandémie de COVID-19 et des mesures de confinement en France », Paris, Policy Brief n°65, 30 mars 2020.

First, the supply shock is obviously treated as residual. We think that is misunderstanding logics for a lock-down economy, reacting much closer to a war economy than to a civil-time one. An ample literature exists on this topic[11]. As a result of this misunderstanding of the situation, the OFCE reaches a slightly smaller (-2,6% against -3% for INSEE) result for shock consequences on one month.

Table 4

Comparison between INSEE and OFCE estimates

| Duration of lock-down | INSEE | OFCE |

| One month | -3,0% | -2,6% |

| Two month | -6,0% |

Source: INSEE Source: INSEE, https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4471804 and OFCE, « Evaluation au 30 mars 2020 d l’impact économique de la pandémie de COVID-19 et des mesures de confinement en France », Paris, Policy Brief n°65, 30 mars 2020.

As has been said, both these estimates are probably, how bleak they could be, still too optimistic. If we include the production losses, which come from the fact that the efficiency of telework is less than that of “direct” work, losses induced by the fact that agriculture and the food industry will lack seasonal labour, that the return to work ‘activity can only be progressive, we understand that the longer the duration of confinement and the greater the losses per week. The estimates made at the Center for the Study of Industrialization Pattern (CEMI – Robert de Sorbon Center) reveal more pessimistic hypotheses. We also added in these hypotheses, as in those made by INSEE, the inevitable production losses in the period of « de-lock down ».

Table 5

Global lock-down losses in GDP percent

| INSEE | CEMI

Assumption 1 |

CEMI

Assumption 2 |

|

| Assuming 6 weeks of lock-down | -6,5% | -8,2% | -7,6% |

| Assuming 8 weeks of lock-down | -8,0% | -10,3% | -9,7% |

Source : CEMI

CEMI-1: Assuming a constant level of losses by weeks.

CEMI-2: Assuming a progression of losses with passing weeks.

We can therefore estimate that the losses for the year 2020 would be greater than what INSEE estimated by at least 1,1% (for 6 weeks) or 1,7% (for 8 weeks) and could range from -7.6% for six weeks to -10.3 for eight weeks.

Such a shock, which has been without equivalent for the French economy since 1945, will have disastrous consequences on employment. The rise in unemployment could reach between 500,000 and 1 million people, depending on the nature of the measures taken to avoid a disaster in SMEs and very small businesses. The risk is therefore real, given the measures modifying access to unemployment insurance system, which came into force on January 1, 2020, that the French economy would enter a cycle of recession-depression.

Hence, even if non-pharmaceutical intervention could ease the situation by comparison with countries or with cities not applying such measures, they have their cost on their own[12]. Conditions for exiting the lock-down situation are then of the utmost relevance.

3. Questions about leaving lock-down situation

Two questions are important here, the recovering of supply (production), but also the reconstitution of demand[13].

The question of recovering supply has a double dimension, internal and external. From an internal point of view, and assuming that the lock-down is lifted on the same date throughout the metropolitan territory, the main question will lie in the capacity of SMEs and VSEs to resume their activity, after having stayed between 6 weeks to 8 weeks idle and without cash receipts. From an external point of view, a large part of the countries exporting to France have the same problems as we do. The end of the lock-down situation will certainly not be on the same date depending on these countries. The de-synchronization of the return to activity is raising the risk of seriously disrupting given production chains. The example that immediately comes to mind, and by no means the only one, is the automotive industry. Given that the countries of central and Eastern Europe are, for the time being, relatively less affected than France, Italy and Spain, we can think that they will emerge from the lock-down procedures – more or less strict – after us. It is therefore clear that in many branches, production will not be able to return to its level before lock-down for several weeks, even several months.

The question of reconstituting demand also has an internal component and an external component. As for the internal aspect, the question of consumer psychology will weigh heavily. However, this psychology is not the same according to the different social positions, the conditions of lock-down, level of education. If we can reasonably anticipate a burst of consumption in the immediate post-lock-down period, as we can see now in China and as we saw in the post-war period, it is far from certain that it will be sustainable. Some of the consumption, travel, holidays, can no longer take place in the same way and must, at least in part, be carried over to the year 2021. The consumption of durable goods will be subject to trade-off with the constitution of precautionary cash and an increase of saving[14]. Here, government responsibility will be important. If he announces measures suggesting that households may have to pay part of the cost of containment, and if he is preparing a possible return of the epidemic with the same incompetence that he demonstrated in February and early March at the arrival of the Covid-19, we can fear that the volume of this precautionary savings would be very large as it was demonstrated in other pandemics[15].

As for the external component, we should understand that France realizes around 29% of its GDP from exports. What will be the foreign demand? If we can imagine that the demand for luxury goods will be relatively little affected, the same is not true for transport equipment, for example. This fall, or this very slow recovery, in external demand will penalize the recovery of some of the branches of the French economy. Consumption will not automatically recover its volume, or its composition, from the pre-containment. Again, this could significantly delay the economy’s “return to normal”.

It will therefore take at least 2 months, and perhaps 6, for the French economy to return to its normal level of activity, if it has to find it again. Because, there is a real risk, which could be aggravated if the government implements an unsuitable macroeconomic policy, that the economy locks itself in a depressive equilibrium, standing steadily at a level below 1% to 2% to that reached in 2019. The figures that can be estimated at the moment are therefore likely to be increased.

4. Government responses

The government is committed to guaranteeing the wages of employees through what is called “partial unemployment” benefits, and that means that the ASSEDICs will have to go out around 1.3-1,5 billions per week. The government has pledged too to guarantee loans and to help companies overall. It wants to inject 45 billion euros into the economy in direct spending, and 300 billion in financial guarantees[16]. However, these figures remain below needs. There is no doubt that they will be greatly exceeded, and all the more so since confinement will last a long time. Direct spending could reach 60 billion or more. Financial guarantees around 450 billion. In addition, the government will lose revenue (VAT, income tax) due to the sharp drop in activity. He predicts today that the budget deficit could reach 3.9% and not 2.2% of GDP[17]. But, in reality, the total budget deficit should be much higher. Mr Alberic de Montgolfier the head of the French Senate budget committee is already speaking of a deficit of -6,2%[18].

One could estimate the probable budget deficit induced by the pandemic:

Table 6

Budget consequences of the Covid-19

| INSEE | CEMI

Assumption 1 |

CEMI

Assumption 2 |

|

| Losses in GDP (Six weeks of lock-down) | -6,5% | -8,2% | -7,6% |

| Losses in GDP (Eight weeks of lock-down) | -8,0% | -10,3% | -9,7% |

| Losses in budget income (6 weeks) in bln euros** | -81,6 | -102,9 | -95,4 |

| Losses in budget income (8 weeks) in bln euros | -100,4 | -129,3 | -121,7 |

| New expenditures (6 weeks) in bln euros# | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| New expenditures (8 weeks) in bln euros ## | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Additional deficit (6 weeks) in bln euros | -126,6 | -147,9 | -140,4 |

| Additional deficit (8 weeks) in bln euros | -160,4 | -189,3 | -181,7 |

| Forecasted deficit in the finance law in bln euros | -54,5 | -54,5 | -54,5 |

| Forecasted deficit in the finance law in GDP% | -2,2% | -2,2% | -2,2% |

| Total deficit (6 weeks) in bln euros | -181,1 | -202,4 | -194,9 |

| Total deficit (8 weeks) in bln euros | -214,9 | -243,8 | -236,2 |

| Total deficit (6 weeks) in GDP% * | -7,9% | -9,0% | -8,6% |

| Total deficit (8 weeks) in GDP% * | -9,6% | -11,0% | -10,6% |

# Forecasted amount

## Deduced amount if lock-down pushed to 8 weeks

* With GDP volume adjusted to estimates.

** Income losses for all sectors.

If one adds the different assumption made here the total budget deficit for the 2020 fiscal year is to be closer to -8% to -10% of GDP than to the -3,9% announced by the French government.

But, the budget deficit is not what raises now concerns. The main question is to know how the French economy could exit from the lock-down with the minimum of pain. It is therefore important that the government reserves part of the consumption of public administrations for SMEs and VSEs, to provide them with the conditions for a good restart[19]. Like what is done in the United States with the Small Business Act, about 30% of public orders should be reserved for SMEs and VSEs working in France. The government must then make sure that no big business goes bankrupt. Bruno Le Maire, the Minister of Economy, raised the possibility of nationalization[20]. They must be carried out whenever the survival of the company is in question and the risk of significant job losses is present. The Italian government has already begun the nationalization process with the Alitalia air transportation company[21]. Finally, it will have to provide an income guarantee to households, while the economy is back on track.

Beyond that, this epidemic made it clear to political leaders that it is no longer possible to depend at the point where we were, on foreign imports. For all strategic products, in the health sector but also elsewhere, 50% of national consumption should be satisfied by national production. This would allow, if trade relations would again be interrupted, to be able to rapidly increase the production of domestic producers. This implies close monitoring of production capacities, but also a subsidy and price system in order to guarantee this strategic production reserve.

5. How to fund the pandemic and its consequences?

In the medium term, the arbitration for the various governments will be between the speed of a « return to normal » of the economy and additional debt. The conditions for breaking out of confinement will certainly be more difficult than what is expected today, and the subsidies, both to households and to businesses, will have to be massive. In this situation, if the debt issue is not resolved by the end of the year, it will weigh heavily on the economic conditions of 2021 and beyond. The risk is that the exogenous shock of the epidemic will then be followed by an endogenous recessionary shock of budgetary origin. Indeed, the amount of debts is today such that it is excluded, except to cause a new depression with its political consequences, to make pay these debts by the households. The idea put forward by Ms Christine Lagarde and the IMF in 2013 of an authoritarian levy of 10% of savings would also have significant depressive effects[22], because households would like to replenish their savings as quickly as possible and would severely limit their consumption[23]. Huge losses experienced in stock markets are indeed already pushing the economy in this direction.

What could be possible solutions? The idea of using special pandemic European bonds, called “coronabonds” has been plainly refused by Germany[24]. So was the Italian proposal to use the European Solidarity Mechanism (ESM) but without constraints usually imposed by such a mechanism[25]. This too was refused by Germany.

A direct monetary funding done by European Central Bank, could in a way ease the situation. The PEPP or Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Program decided (for a total of 750 bln euros) on March 24th is clearly a step in the good direction[26]. But, funding problems are probably to stay with us for a quite long period. The “temporary” nature of this program is probably to be extended and the ceiling so far decided probably exceeded. A significant issue is the fact that the ECB has lifted the 33% of a given country limit in its new sovereign securities purchasing program. This limit had been decided after a 2018 judgement of the European Union Justice Court, following a complaint filed by Germany. The future of the PEPP looks then hung in balance with a possible new judicial action from Germany[27].

What would be long-term consequences? Could the ECB be transformed in a kind of defeasance fund for sovereign debts? The possible consequences for the Eurozone are clearly disturbing for the government and for those supporting the Euro.

This crisis is much more serious than the 2008 one. In addition, the 2008 crisis was initially financial and then it affected the production sector. The current crisis starts with the shutdown or the dormancy of part of the production due to containment. The drop in production figures is closer to the level of the 1929 crisis. But what is new is the speed with which production is almost at a standstill. So this is an unprecedented crisis. It will profoundly change the attitude of the people and, hopefully, of those in power.

Annex 1

From INSEE data about the French GDP disaggregation we constructed the following table.

AT1

| GDP at current prices (billions euros) | 2018 | 2019 | Week |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 38,2 | 39,0 | 0,750 |

| Manufacturing, mining and other industries | 280,2 | 286,4 | 5,508 |

| Extractive industries, energy, water, waste management and depollution | 51,8 | 53,0 | 1,019 |

| Extractive industries | 1,9 | 1,9 | 0,037 |

| Production and distribution of electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning | 34,7 | 35,5 | 0,683 |

| Water production and distribution; sanitation, waste management and depollution | 15,2 | 15,5 | 0,299 |

| Manufacture of food, beverages and tobacco products | 41,7 | 42,6 | 0,820 |

| Coking and refining | 5,0 | 5,1 | 0,099 |

| Manufacture of electrical, electronic and computer equipment; machinery manufacturing | 30,9 | 31,5 | 0,606 |

| Computer, electronic and optical product manufacturing | 12,5 | 12,8 | 0,246 |

| Manufacture of electrical equipment | 6,6 | 6,8 | 0,130 |

| Manufacture of machinery and equipment n.e.c. | 11,7 | 12,0 | 0,230 |

| Transport equipment manufacturing | 27,7 | 28,3 | 0,545 |

| Manufacture of other industrial products | 123,1 | 125,8 | 2,419 |

| Textile manufacturing, clothing industries, leather and footwear industry | 4,8 | 4,9 | 0,094 |

| Woodworking, paper and printing industries | 12,0 | 12,3 | 0,237 |

| Chemical industry | 19,3 | 19,7 | 0,379 |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 12,4 | 12,6 | 0,243 |

| Rubber, plastic and other non-metallic mineral product manufacturing | 18,7 | 19,1 | 0,367 |

| Metallurgy and manufacture of metal products, excluding machinery and equipment | 26,8 | 27,4 | 0,528 |

| Other manufacturing industries; repair and installation of machinery and equipment | 29,1 | 29,7 | 0,572 |

| Construction | 117,4 | 120,0 | 2,308 |

| Mainly market services | 1 187,7 | 1213,9 | 23,345 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation and catering | 371,8 | 380,1 | 7,309 |

| Trade ; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 216,2 | 221,0 | 4,250 |

| Transport and storage | 94,0 | 96,1 | 1,848 |

| Accommodation and catering | 61,7 | 63,0 | 1,212 |

| Information and communication | 112,0 | 114,4 | 2,201 |

| Publishing, audiovisual and broadcasting | 25,6 | 26,1 | 0,502 |

| Telecommunications | 24,9 | 25,5 | 0,490 |

| IT activities and information services | 61,5 | 62,8 | 1,208 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 80,6 | 82,4 | 1,585 |

| Real estate activities | 269,9 | 275,9 | 5,305 |

| Scientific and technical activities; administrative and support services | 292,9 | 299,4 | 5,757 |

| Legal, accounting, management, architecture, engineering, control and technical analysis activities | 116,3 | 118,9 | 2,287 |

| Scientific research and development | 37,3 | 38,2 | 0,734 |

| Other specialized, scientific and technical activities | 16,6 | 17,0 | 0,326 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 122,6 | 125,3 | 2,410 |

| Other services | 60,4 | 61,7 | 1,187 |

| Arts, shows and recreational activities | 29,3 | 29,9 | 0,575 |

| Other service activities | 28,2 | 28,8 | 0,554 |

| Activities of households as employers | 3,0 | 3,0 | 0,058 |

| Mainly non-market services (*) | 467,5 | 477,8 | 9,189 |

| Public administration and defense – compulsory social security | 163,2 | 166,8 | 3,209 |

| Education | 112,5 | 114,9 | 2,210 |

| Human health activities | 123,0 | 125,8 | 2,419 |

| Medico-social and social accommodation and social work without accommodation | 68,7 | 70,3 | 1,351 |

| Total branches | 2 090,9 | 2137,2 | 41,100 |

From Table AT-1 we deduced the simplified table AT-2

AT-2

| Weekly production – 2019 | CEMI – Assumption

|

Weekly value | |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 0,75 | 0,880 | 0,66 |

| Manufacturing, mining and other industries | 5,51 | 0,567 | 3,12 |

| Extractive industries, energy, water, waste management and depollution | 1,02 | 0,850 | 0,87 |

| Manufacture of food, beverages and tobacco products | 0,82 | 0,950 | 0,78 |

| Coking and refining | 0,10 | 0,700 | 0,07 |

| Manufacture of electrical, electronic and computer equipment; machinery manufacturing | 0,61 | 0,300 | 0,18 |

| Transport equipment manufacturing | 0,54 | 0,250 | 0,14 |

| Textile manufacturing, clothing industries, leather and footwear industry | 0,09 | 0,250 | 0,02 |

| Woodworking, paper and printing industries | 0,24 | 0,400 | 0,09 |

| Chemical industry | 0,38 | 0,500 | 0,19 |

| Pharmaceutical industry | 0,24 | 1,000 | 0,24 |

| Rubber, plastic and other non-metallic mineral product manufacturing | 0,37 | 0,600 | 0,22 |

| Metallurgy and manufacture of metal products, excluding machinery and equipment | 0,53 | 0,330 | 0,17 |

| Other manufacturing industries; repair and installation of machinery and equipment | 0,57 | 0,250 | 0,14 |

| Construction | 2,31 | 0,110 | 0,25 |

| Mainly market services | 23,34 | 0,733 | 17,1 |

| Trade ; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 4,25 | 0,400 | 1,70 |

| Transport and storage | 1,85 | 0,660 | 1,22 |

| Accommodation and catering | 1,21 | 0,150 | 0,18 |

| Information and communication | 2,20 | 0,800 | 1,76 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 1,59 | 0,700 | 1,11 |

| Real estate activities | 5,31 | 0,200 | 1,06 |

| Scientific and technical activities; administrative and support services | 5,76 | 0,600 | 3,45 |

| Public administration and defence – compulsory social security | 3,21 | 0,660 | 2,12 |

| Education | 2,21 | 0,330 | 0,73 |

| Human health activities | 2,42 | 1,000 | 2,42 |

| Medico-social and social accommodation and social work without accommodation | 1,35 | 1,000 | 1,35 |

| TOTAL | 41,10 | 0,514 | 21,14 |

The first column gives the weekly production in value (billion euros) in 2019. The second, the estimated level of the activity under confinement (1 = no impact / 0 = total cessation of the activity), and finally the third column gives the production in estimated value under confinement. We then obtain an overall estimate in value of 21.14 billion against 41.10 billion in 2019, i.e. an activity coefficient of 51.4% (loss of 48.6%) against the estimate of INSEE which on a coefficient of 65% (loss of 35%).

Notes

[1] Eichenbaum, M. S., S. Rebelo, and M. Trabandt, The macroeconomics of epidemics, Working Paper n° 26882, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

[2] Markel, H., H. B. Lipman, J. A. Navarro, A. Sloan, J. R. Michalsen, A. M. Stern, and M. S. Cetron, Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic. In Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 298(6), 2007, pp. 644–654.

[3] Garrett, T. A., Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a

Modern-Day Pandemic, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2007. Brainerd, E. and M. V. Siegler, The Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic, CEPR Discussion Papers n°3791, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers, 2003.

[4] Hatchett, R. J., C. E. Mecher, and M. Lipsitch, « Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic », in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 104(18), 2007, pp. 7582–7587

[5] https://www.insee.fr/fr/information/4471804

[6] OFCE, « Evaluation au 30 mars 2020 d l’impact économique de la pandémie de COVID-19 et des mesures de confinement en France », Paris, Policy Brief n°65, 30 mars 2020.

[7] https://blogs.imf.org/2020/03/20/blunting-the-impact-and-hard-choices-early-lessons-from-china/

[8] https://blogs.imf.org/2020/03/20/blunting-the-impact-and-hard-choices-early-lessons-from-china/

[9] https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/01/economic-policies-for-the-covid-19-war/

[10] For a more precise discussion on INSEE estimates : https://www.les-crises.fr/russeurope-en-exil-lhypothese-blanche-neige-les-previsions-de-linsee-et-leur-discussion-par-jacques-sapir/

[11] We are just to quote Milward A.S., War, Economy and Society, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1977 : Hardach G., The First World War, 1914-1918, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1977 ; Fridenson P. et Griset P.,(dir), L’industrie dans la Grande Guerre, Paris, Comité pour l’Histoire Economique et Financière de la France, 552 p ; Feldman G.D., Army, Industry and Labor in Germany, 1914-1918, Princeton (NJ), Princeton University Presse, 1966.

[12] Correia S., S. Luck, and E. Verner, Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu, Draft, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, March 30th, 2020.

[13] See the Op-ed paper written in the digital newspaper « La Tribune »: www.latribune.fr/opinions/tribunes/covid-19-choc-d-offre-ou-choc-de-demande-rate-les-deux-843729.html

[14] Nakamura E., J. Steinsson, R. Barro and J-F Ursua, « Crises and Recoveries in an Empirical Model of Consumption Disaster », in American Economic Journal, Macroeconomics, n°5, 2013, pp. 35-73.

[15] Jorda O., Singh S.R., Taylor A.M., « Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics », San Francisco, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper Series, Working Paper 2020-09, March 30th, 2020, https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2020-09

[16] https://www.economie.gouv.fr/coronavirus-soutien-entreprises

[17] https://www.lesechos.fr/economie-france/budget-fiscalite/coronavirus-le-deficit-public-va-se-creuser-dans-des-proportions-encore-inconnues-1186670

[18] https://www.lesechos.fr/economie-france/budget-fiscalite/coronavirus-pourquoi-le-deficit-public-va-encore-saggraver-1188109

[19] http://www.cci-paris-idf.fr/informations-territoriales/ile-de-france/actualites/aider-entreprises-surmonter-epidemie-coronavirus-ile-de-france

[20] https://www.ouest-france.fr/sante/virus/coronavirus/coronavirus-les-eventuelles-nationalisations-d-entreprises-seront-temporaires-6799107

[21] https://www.latribune.fr/economie/france/coronavirus-le-retour-des-nationalisations-842721.html

[22] https://www.lefigaro.fr/conjoncture/2013/10/09/20002-20131009ARTFIG00524-le-fmi-propose-une-supertaxe-sur-le-capital.php

[23] This would be a kind of reverse « wealth effect », Ando, A. and F. Modigliani, “The ‘Life Cycle’ Hypothesis of Saving: AggregateImplications and Tests”, in American Economic Review, vol. 53, n°1, 1963, pp. 55-84, Arena, J.J., “Capital Gains and the ‘Life Cycle’ Hypothesis of Saving, in American Economic Review, vol. 54, n°1, 1964, pp. 107-111, Ando, A., “Reflections on Some Recent Evidence on Life Cycle Hypothesis of Saving”, in Studies in Banking and Finance, n° 5, 1988, pp. 7-25

[24] https://www.capital.fr/entreprises-marches/lallemagne-soppose-aux-coronabonds-souhaites-par-la-france-et-litalie-contre-la-crise-1365932

[25] https://www.lopinion.fr/edition/economie/zone-euro-l-italie-reclame-recours-conditions-mes-215003

[26] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/legal/date/2020/html/index.en.html?skey=ECB/2020/17

[27] https://www.usinenouvelle.com/article/coronavirus-la-bce-suspend-ses-limites-aux-rachats-de-dette-souveraine.N946181

1 réactions et commentaires

Merci. Enfin un texte en anglais que j’ai pu lire sans difficulté (traduit par… un français)!

« The idea put forward by Ms Christine Lagarde and the IMF in 2013 of an authoritarian levy of 10% of savings would also have significant depressive effects[22], because households would like to replenish their savings as quickly as possible and would severely limit their consumption[23].

Je trouve l’idée d’une ponction de l’épargne (assurances vies en particulier) très intéressante et justifiée moralement : l’économie a été sacrifiée à la survie des personnes âgées… qui sont celles dont l’épargne est la plus abondante. Un moyen donc d’amortir un peu les consèquences de l’effondrement économique sur l’endettement, alors que les privatisations tant vantées, ne sont plus possibles pour un certain temps.

+0

AlerterLes commentaires sont fermés.